BE THE FIRST TO GET PRODUCT UPDATES

Get notified about new features & special offers......

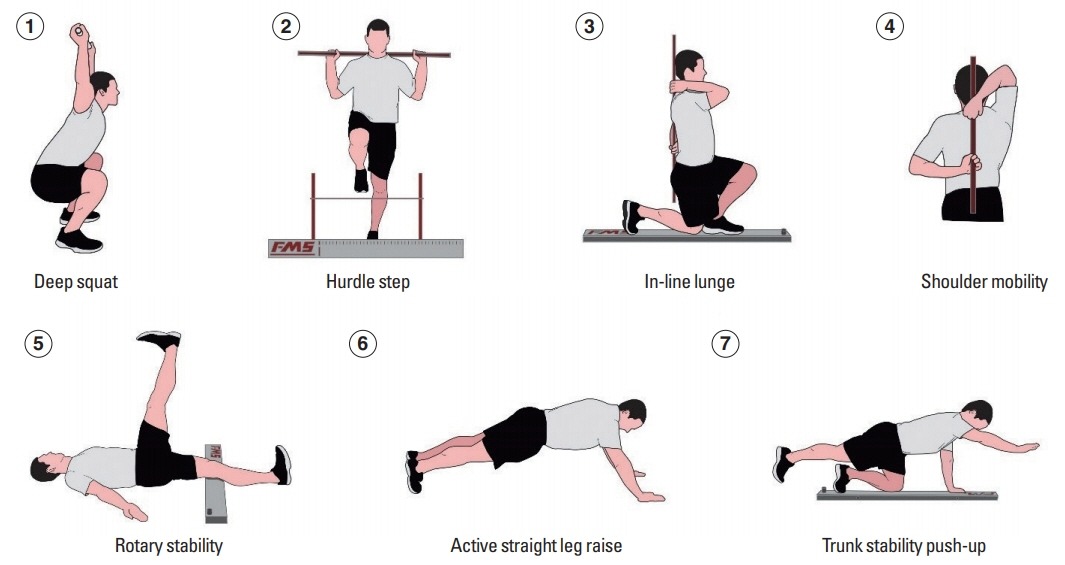

Movement screening and assessment helps coaches identify imbalances or mobility limitations in fundamental movement patterns. The Functional Movement Screen (FMS) is one of the most widely used movement assessment tools for this purpose. It breaks movements into key tests (e.g., squat, hurdle step, in-line lunge) and uses a standardized scoring sheet to record performance. Professional and collegiate sports teams, as well as the military, use the FMS to highlight issues early and reduce injury risk through athlete screening [1]. By understanding how an athlete moves, coaches can design more effective warm-ups, corrective exercise programs, and training plans.

Figure 1. The 7 Functional Movement Screen tests [2]

The FMS is a seven-test battery designed to assess fundamental movement abilities [1]. It covers patterns such as the deep squat, hurdle step, in-line lunge, and shoulder mobility [3]. Each test is scored on a 0–3 scale using the Functional Movement Screen scoring sheet [3]:

Criteria

Description

An athlete's total FMS score (0–21) reflects overall movement quality. The goal is not to pass or fail, but to identify asymmetries, stability deficits, or mobility restrictions that could impact performance or injury risk.

Beyond the Numbers: The Importance of Descriptive Notes

While the numeric score provides a baseline, effective FMS administration requires detailed notes on observed compensations [3]. Practitioners should document what compensations occurred (e.g., heels lifting, knee valgus), where they originated (e.g., limited ankle mobility, hip tightness), and any left-right asymmetries. These descriptive notes identify the underlying causes of dysfunction and directly inform corrective exercise strategies.

Coaches often ask: Is the FMS valid? Does the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) predict injury risk?

Research suggests the FMS demonstrates excellent reliability but mixed predictive validity. A 2017 meta-analysis reported strong inter- and intra-rater reliability (ICC ≈ 0.81) and noted that athletes scoring ≤14 were about 2.7 times more likely to sustain an injury [1].

However, systematic reviews caution against relying solely on FMS scores for injury prediction. Moran et al. concluded that the link between FMS results and injury was weak [3]. In other words, a low score may flag current dysfunctions but does not guarantee or predict future injury. For best practice, the FMS should be combined with other measures, such as injury history, strength testing, and workload monitoring, for a more complete risk profile.

While useful for sports performance testing, the FMS has limitations:

Subjectivity: Scores can vary between raters. Although reliability is strong overall, less experienced practitioners may grade inconsistently [3]. Attempts have been made to correct this through FMS certification programs to align scoring standards. However, many practitioners administering the tests in real-world settings are not FMS certified, reducing the standardization and consistency of athlete screening results.

No single "key" test: All seven movement patterns provide unique insights. However, there are instances of elite Olympic weightlifters able to snatch over 100kg achieving a "fail" in the overhead squat. Further detail is still required after the grading to understand said limitations.

Context matters: Low scores highlight deficits, but coaches should prioritize major dysfunctions rather than small imperfections.

Figure 2. Output Sport IMU sensor capturing real-time movement data during athlete screening

Advances in technology now allow coaches to go beyond visual assessments through biomechanical assessment. Markerless motion-capture systems (camera-based) and wearable sensors (IMUs) enable you to measure joint angles, range of motion, balance, and stability [4], [5].

Wearable IMUs are particularly practical for coaches. Research shows that IMU-based systems demonstrate excellent accuracy (>86%) for measuring joint angles and range of motion [7], [8]. The Output Sports sensor is an IMU device that attaches to the body or barbell to capture movement in real time, measuring squat speed, depth, or joint range during actual training. This brings lab-grade analysis into everyday training environments.

Objective digital tools enhance traditional movement screens by offering:

Consistency: Sensors eliminate human bias. A system will always return the same measurement under the same conditions [9].

Precision: Exact measurements, such as squat depth or joint angles, highlight subtle changes in performance [6].

Versatility: Systems can assess both isolated joints (e.g., ankle dorsiflexion ROM) and complex patterns (e.g., loaded squats, Olympic lifts) during actual training sessions.

Progress tracking: Hard numbers show real improvements. For example, documenting a 15% increase in squat velocity after a training block provides clear evidence for athletes and coaches alike.

A practical workflow for comprehensive athlete screening might look like this:

Needs Analysis & Injury Epidemiology – Understand the sport's specific demands and identify common injury patterns. What movements matter most? What joints are frequently injured in this population?

Use IMUs to Identify Joint by Joint and Then in the Movement Itself – The beauty of sensors like the Output Sports sensor is that they can be used in a joint-by-joint approach and then in the full movement with load to see where issues arise. Objectively measure mobility, stability, strength, and power under actual training loads.

Analyze Data – Compare results to sport-specific norms or established benchmarks. Identify asymmetries that may increase injury likelihood and deficits such as limited hip flexion, reduced squat depth, or low velocity outputs.

Implement Tailored Interventions – Prescribe targeted corrective exercise based on findings (e.g., mobility drills, core stability work, or velocity-based training progressions).

Re-screen – Repeat tests after 4-8 weeks to determine whether improvements have occurred. If progress is insufficient, adjust the strategy and continue monitoring.

Movement first: Always assess how someone moves before prescribing training.

FMS is a tool, not a verdict: It identifies broad movement issues but should not be used as a sole predictor of injury [1], [3].

Embrace digital: Wearable IMU sensors add objectivity, with studies reporting ICCs >0.90 and accuracy >86% [7], [8].

Objectivity wins: Quantifying ROM, stability, velocity, and performance removes subjectivity and builds trust [9].

Combine approaches: The best practice is pairing a coach's observational expertise with precise digital metrics for a full picture of movement health.

What is a good FMS score for athletes? A score of 14 or below has been associated with increased injury risk in some studies [1]. However, scores should be interpreted in context with the athlete's sport, training history, and individual movement patterns rather than as absolute pass/fail thresholds.

Can FMS prevent injuries? The FMS itself doesn't prevent injuries—it identifies movement limitations and asymmetries. When combined with appropriate corrective exercise interventions and ongoing monitoring, movement screening can be part of a comprehensive injury risk reduction strategy [1], [3].

How often should athletes be screened? Most programs conduct movement assessment at the beginning of a season or training phase, then re-screen every 4-8 weeks or after corrective interventions. The frequency depends on the sport's injury risk, training intensity, and available resources.

Do I need FMS certification to use movement screening? While FMS certification can improve scoring consistency and standardization, coaches can implement movement assessment protocols using various tools. Digital systems like IMU sensors provide objective measurements that don't require certification [7], [8], [9].

[1] R. A. Bonazza, C. Smuin, B. Onks, R. R. Silvis, and S. Dhawan, "Reliability, Validity, and Injury Predictive Value of the Functional Movement Screen: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis," Am J Sports Med., vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 725–732, 2017. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27159297/

[2] M. H. Kang, D. K. Lee, and J. S. Oh, "The Functional Movement Screen total score and physical performance in elite male collegiate soccer players," Exercise Science, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 403-412, 2013. doi: 10.15857/ksep.2013.22.4.403

[3] Physiopedia, "Functional Movement Screen (FMS)," 2024. Available: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Functional_Movement_Screen_(FMS)

[4] D. Kanko, et al., "Markerless vision-based functional movement screening movements evaluation with deep neural networks," Comput Biol Med., vol. 165, 2023. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38222112/

[5] A. Camomilla, et al., "Reliability of Markerless Motion Capture Systems for Assessing Movement Screenings," J Biomech., vol. 152, 2024. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38476162/

[6] Output Sports, "Guide to Velocity Based Training," 2023. Available: https://www.outputsports.com/blog/guide-to-velocity-based-training

[7] J. Courel-Ibáñez, et al., "Validity and Reliability of the Inertial Measurement Unit for Barbell Velocity Assessments: A Systematic Review," Sensors, vol. 21, no. 7, 2021. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33916801/

[8] A. R. Araujo-Gomes, et al., "Validity and Reliability of Wearable Sensors for Joint Angle Estimation: A Systematic Review," Sensors, vol. 19, no. 8, 2019. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6479822/

[9] M. R. Camomilla, et al., "Trends Supporting the In-Field Use of Wearable Inertial Sensors for Sport Performance Evaluation: A Systematic Review," Sensors, vol. 18, no. 3, 2018. Available: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5877384/